Yes She Can – Women & Leadership

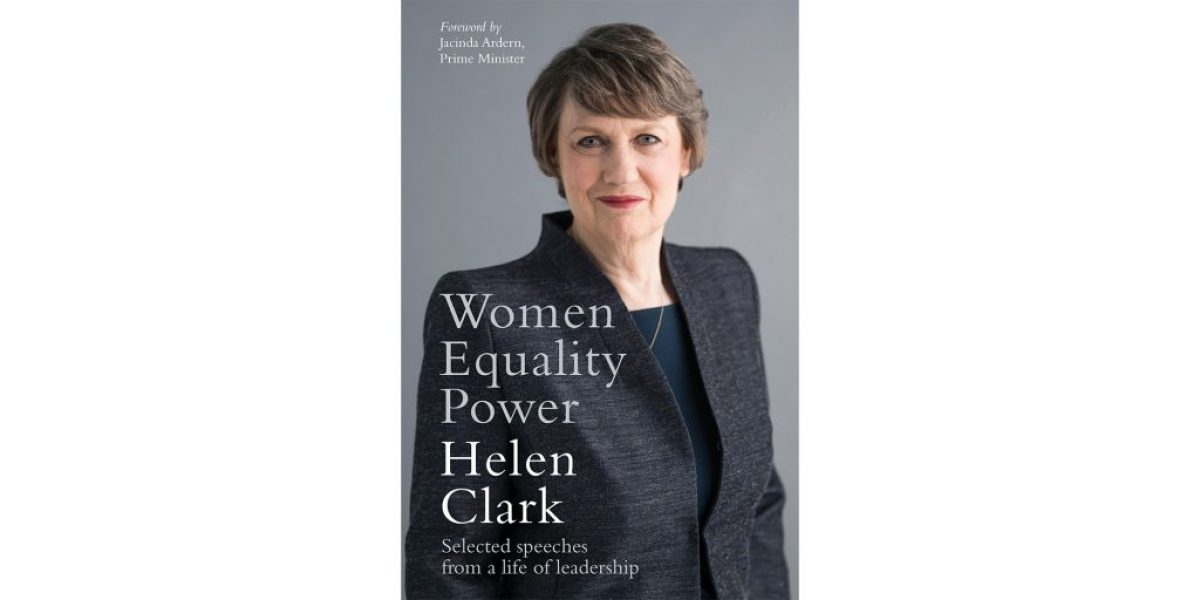

From a powerful selection of speeches from a life of leadership, Helen Clark shares with us this still relevant TEDx talk from 2013. AOTEA CENTRE, AUCKLAND – 3 AUGUST 2013 TED is anon-profit organisation famous for short, interesting and clever talks no longer than eighteen minutes that cover a broad spectrum of topics. Every year…