The Women Literally Shaping Our World: Yvonne Farrell & Shelley McNamara

Pictures Courtesy of the Pritzker Architecture Prize

Architecture often celebrates the individual, usually male, “starchitect”, but Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara have worked together in equal collaboration where authorship is shared and decisions are argued through rather than imposed for the last 50 years. In the process, they have scooped up some of the world’s most prestigious architecture awards and helped shape our relationship with architecture and the resulting buildings.

They met as students at University College Dublin in the early 1970s, graduating in 1974 into a profession that was overwhelmingly male. In 1978 they founded Grafton Architects, named after the street where they opened their first office, and began combining practice with teaching. That dual focus has run through their entire career. They have taught generations of students in Ireland and abroad while steadily taking on public, educational and cultural commissions that would come to define their practice.

Their breakthrough on the global stage came with the Università Luigi Bocconi School of Economics in Milan, completed in 2008. The building’s deep public base and powerful concrete forms impressed juries and critics alike. It was named World Building of the Year at the inaugural World Architecture Festival, beating much larger and better-known practices. That recognition was followed by a string of international honours: in 2016 their campus for the Universidad de Ingeniería y Tecnología (UTEC) in Lima won the first-ever RIBA International Prize, praised for its response to a difficult urban site and its use of open terraces to harness the local climate.

By 2019, the profession was starting to acknowledge the full depth of their contribution. The Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland awarded them the James Gandon Medal for Lifetime Achievement, its highest honour. That same year, the Royal Institute of British Architects announced that Grafton Architects would receive the 2020 RIBA Royal Gold Medal, the UK’s top architecture award, approved by the monarch. It was only the second time in the medal’s 170-plus year history that the prize had gone to a women-led firm, and the first time it had been awarded to an all-female pair.

The most high-profile recognition arrived in 2020, when Farrell and McNamara were named Pritzker Architecture Prize laureates. The jury highlighted their integrity, their collaborative way of practising, their strong sense of place and their ability to make buildings that are both modern and deeply rooted in their context. It also acknowledged that their work consistently serves people and cities rather than seeking attention for its own sake. In 2022 they were recognised again, this time for a quality that runs quietly through their work: light. The Daylight Award named them its architecture laureates, noting their mastery of daylight to create legible, humane spaces in complex buildings.

Alongside these awards, Farrell and McNamara have also helped shape the global conversation about architecture. In 2018 they were appointed co-curators of the Venice Architecture Biennale, one of the field’s most important events. Their theme, “Freespace”, invited architects around the world to focus on generosity, public value and the quality of space that is freely shared rather than commercially driven.

Farrell and McNamara treat architecture as a framework for human life rather than a series of isolated objects. In interviews, McNamara has described architecture as something that anchors us and connects us to the world, while Farrell has called it one of the most complex cultural activities we have and an enormous privilege. Their projects begin with close attention to place: the geography of an Irish city street, the topography of a Lima ravine, the climate of a French campus. They work with robust materials and use section, proportion and daylight to keep even large institutional buildings at a human scale.

UTEC in Lima is a good example. The site lies between a sunken highway and a residential neighbourhood. Rather than sealing itself off, the building steps and terraces upwards, creating outdoor teaching and social spaces that catch coastal breezes and reduce the need for air-conditioning. In Dublin, their Department of Finance building uses thick local limestone panels, recessed openings and carefully detailed bronze gates to give a sense of solidity and public seriousness, while still bringing light and air deep into the plan.

Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara have spent more than four decades proving that architecture can be ambitious without losing sight of the people who use it. Their studio combines design, teaching and research, and they have mentored generations of younger architects, including many women who now lead practices of their own.

Offices for the Department of Finance

2009, Dublin, Ireland. Photo courtesy of Dennis Gilbert

Located on a complex site in central Dublin, the Offices for the Department of Finance respond to the layered context of St Stephen’s Green, the Huguenot Cemetery and surrounding Georgian streets. The six-storey building, plus basement, brings Department staff together in a single location and continues a Dublin tradition where significant buildings negotiate shifts in scale at key points in the streetscape. A restrained but careful palette of materials gives the building its sense of solidity and quiet dignity, most notably the handcrafted bronze entrance gate and Irish limestone façades. Inside, a main staircase set near the Merrion Row elevation softens harsh sunlight and buffers city noise. Unusually for Dublin, the building has exposures on all sides, offering panoramic views and changing light from every window, and maintaining a strong visual connection between those working inside and the city outside.

Università Luigi Bocconi

2008, Milan, Italy. Photo courtesy of Federico Brunetti

Occupying an entire city block, this project reads more like a vertical campus of pavilions and courtyards than a single building. Conference halls, lecture theatres, offices, meeting rooms, a library and a café together accommodate around 1,000 professors and students, fostering a strong sense of community while sitting comfortably within the surrounding city. Throughout, generous and varied open spaces invite spontaneous encounters and exchanges. Winner of the World Building of the Year 2008 award, the stone-clad complex can be understood as three main parts: the sunken volume, which houses the impressive aula magna; the flowing, open ground floor; and the more functional “floating” boxes above. The aula magna occupies the main frontage, giving the building a clear symbolic presence.

Medical School, University of Limerick

2012, Limerick, Ireland

Straddling both sides of the River Shannon, the Medical School at the University of Limerick forms part of the university’s continuing northward expansion. Linked to the main campus by a pedestrian bridge, the development includes the medical school itself, a sequence of three red-brick residences by the same architects and a new public space that acts as a focal point for the precinct. An outer limestone wall, drawing on a material long associated with the region, is folded, profiled and layered in response to orientation, sun, wind, rain and patterns of public use. The four-storey building is organised around a double-height atrium and a broad, open staircase, allowing views across and between levels and reinforcing a sense of connection throughout the interior.

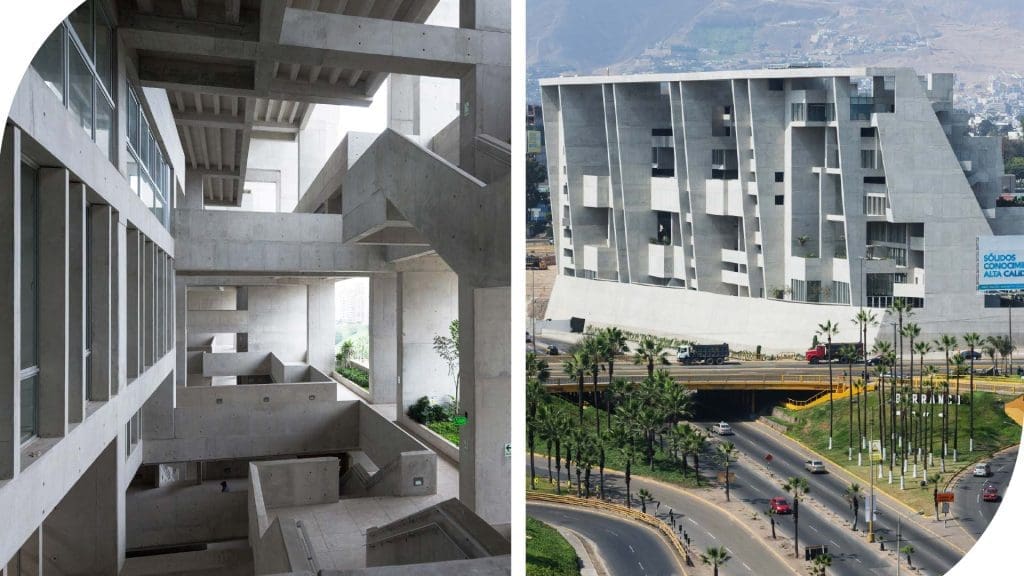

University Campus UTEC Lima

2015, Lima, Peru

Set on a challenging site between a busy motorway and the low-rise edge of the city, the UTEC Lima campus is conceived as a vertical, layered structure inspired by Lima’s coastal cliffs. The north side of the building reads as a new “cliff” along the highway, while the south steps down in terraces, gardens and open spaces to connect with the smaller scale of the surrounding neighbourhood. Raw concrete structure and circulation are closely integrated to form a three-dimensional landscape of ramps, stairs and platforms, creating numerous informal and humane gathering spaces throughout the building. Larger volumes sit closer to the ground, with teaching spaces, administration and staff offices staggered on the upper levels, and a library near the roof offering panoramic views over the city and the sea.

London School of Economics and Political Science – The Marshall Building

2022, London, United Kingdom. Rendering courtesy of Picture Plane

Located on the dense urban campus of the London School of Economics and Political Science at Lincoln’s Inn Fields, at the meeting point of three distinct boroughs, the Marshall Building brings together several business-related academic departments alongside a performing arts facility, multi-purpose halls, a café and shared student spaces. At its heart is the Great Hall, the main point of entry and a generous public space of around 800 square metres designed as flexible civic room for daily use by hundreds of people and for large-scale events such as exhibitions, talks, dinners and open days.

Institut Mines Télécom

2019, Paris, France. Photo courtesy of Alexandre Soria

This 46,200 m² building in Palaiseau houses Institut Mines Télécom, Télécom ParisTech and Télécom SudParis, serving a large community of scholars, professors and students. Generous open spaces, extensive glazing, glass curtain walls and exposed ceilings allow natural light to filter through a sequence of rooms, creating variead impressions of light across both large and intimate areas, and within the interlocking spaces that form five courtyards and a central quadrangle. The master plan introduces streets, squares and boulevards with a carefully integrated landscape and ecological strategy, drawing on the long tradition of educational institutions defined by lawns, quads, cloisters and courtyards, and translating that legacy into a contemporary campus setting.

Parnell Square Cultural Quarter, City Library

Under construction, Dublin, Ireland. Rendering courtesy of Picture Plane

This 8,000 m² city library is designed to serve the 1.2 million people of the Greater Dublin Area and is expected to welcome around 3,000 visitors a day, replacing the nearby Dublin Central Library, which opened in 1986 and no longer meets contemporary needs. The project restores six four-storey-over-basement Georgian houses at 23–28 Parnell Square, incorporates two further houses at 20 and 21, and adds a substantial new building to the rear. The design renews the finely proportioned 18th-century rooms while introducing a memorable 21st-century addition that weaves historic and contemporary elements together. A tiered, multi-level interior with large openings brings daylight deep into the building.