Glen Luchford: The Photographer Every Creative Wants to Be

Pictures Courtesy of © Glen Luchford

Earlier this northern autumn, Milan quietly reminded everyone why it still sets the pace in fashion imagery. At 10 Corso Como, Glen Luchford’s first solo exhibition, Atlas, pulled three decades of work into one space and one mood. It has now wrapped, but the echo of it is still moving through studios, group chats and moodboards everywhere. For anyone in fashion or visual culture, it was a reminder of just how much of our shared visual language can be traced back to one quiet British photographer.

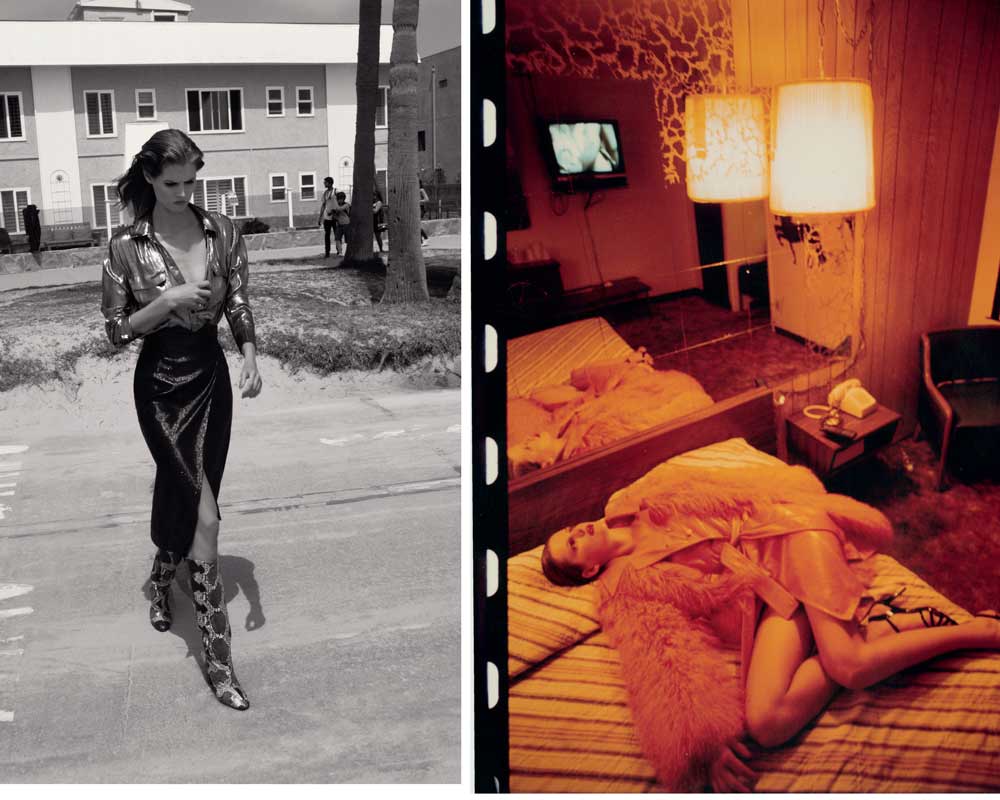

Atlas was never meant to be a polite retrospective. Conceived and designed by Luchford himself, it played out like a slipstream through his head large-format prints, layered works, collages, iconic campaigns, personal images, outtakes and so-called mistakes all piled into one continuous flow. He has described his universe as a “visual orgy,” and the show leaned into that description with intent. You weren’t just looking at finished images; you were dropped into the mess of experimentation that produces them.

For many visitors, there was also a moment of recognition. You might not have known his name, but you had seen his eye. Those moody Prada campaigns from the late 1990s that felt like stills from a European art film. The Gucci images that made luxury look like a strange, beautiful hallucination. The editorials where models look less like mannequins and more like characters caught in the middle of a story. All of that is Luchford.

His path into that position was anything but conventional. He left school young, taught himself photography and first surfaced in the pages of The Face, the cult British style magazine that defined a generation. He started shooting bands, street kids, early Kate Moss. What marked him even then was a sense of cinema in the work the feeling that whatever you were seeing on the page was part of a larger, unseen narrative.

In interviews, he has talked about an early job with a band where he stuck rigidly to his plan and ignored a wilder suggestion from them. The pictures were fine, but not special, and it stung. His takeaway was simple and has guided him ever since you have to be looser on set, more open to what unfolds in front of you. That looseness has become one of his trademarks. His most powerful photographs feel controlled and chaotic at the same time, as if the whole scene might collapse one second after the shutter clicks.

Of course, looseness is only possible if there is serious craft underneath it. Technically, Luchford’s work is meticulous. He is known for building complex lighting setups that create atmosphere rather than just brightness. Instead of freezing everything with a blast of flash, he often uses continuous light sources, longer exposures and just enough movement to keep the frames alive. There is an almost cinematic patience to it lights nudged a fraction, colours of gels shifted slightly, models asked to hold a pose long enough for tension to creep into the body.

On big campaigns in the late 1990s and 2000s, sets could take hours to light and refine before a single usable shot was taken. It is part of why his images feel like film stills rather than traditional fashion shots. The background is never just a backdrop. It is a real space, with its own weather and mood. You sense something has just happened off-camera, or is about to.

That cinematic pull comes directly from his own obsessions. As a child, watching Taxi Driver for the first time was a kind of epiphany. The way a film could make a city feel beautiful, dangerous and lonely all at once hit him hard. Add in teenage years steeped in British punk and skate culture, and you start to understand why his work never looks too polished, even when the clothes are. There is always a little grit at the edges, a feeling that the people in his pictures have lives outside the frame.

The Prada campaigns of the late 1990s are a good example of how all of this converges. Instead of the standard glossy perfection of luxury advertising at the time, he gave Prada murky skies, strange angles, awkward pauses and characters who looked like they were thinking about something other than the bag on their arm. In later years he admitted that even he was surprised by how often people still return to those images, saying there is “something about them that people want to go back to and keep looking at.” That addictive quality lies in the atmosphere more than the clothes.

His work with Gucci under Alessandro Michele did something similar for a new generation. The campaigns looked like fragments of half-forgotten films retro cars, faux sci-fi landscapes, tigers, teenagers and Hollywood references all colliding in one frame. Behind the scenes, he pushed for old-school techniques wherever he could. For one film, inspired by the stop-motion monsters of Ray Harryhausen, the team used practical animation rather than slick CGI. On set, models had to react to a man with a stick and a tennis ball standing in for a dinosaur’s head. The result was imperfect and strange in exactly the right way.

That willingness to blend analogue craft and new technology is very much where Luchford lives now. He is not nostalgic about the past; if anything, he is hungry for what comes next. He has spoken about how digging through his archive can feel tedious, and that he is more excited by new cameras, new formats, new ways of moving images rather than just freezing them. This is part of why Atlas ended with a room of his fashion films, allowing visitors to see how his still image sensibility spills into motion.

Alongside all of this, there is the simple fact of career gravity. Over the last thirty years Luchford has shot for British Vogue, French Vogue, Vanity Fair and countless other titles. He has worked with Prada, Gucci, Yves Saint Laurent, Lanvin, Miu Miu, Chloé, Calvin Klein. His photographs sit in the collections of major museums around the world. Yet he has never lost that slightly outsider energy of the skate kid and film obsessive who taught himself how to make a camera feel like a storytelling tool.

What really makes him the photographer every creative references, though, is not the client list or the museum credentials. It is the way his images have quietly shifted our idea of beauty. Before Luchford, a lot of luxury fashion photography aimed at an impossible, distant perfection. After Luchford, it became easier to show a crease, a shadow, a fleeting expression. He has helped dismantle the idea that fashion imagery has to be smooth and impenetrable, bringing it closer to something everyday and real, without ever losing its magic.

For M2woman readers who care about the culture around fashion as much as the clothes themselves, this is why his recent Milan exhibition mattered. Atlas may have been on for a brief moment in one gallery, but the work inside it has been living in our heads for years. It lives in the lighting references sent around before a shoot, the moodboards taped up in studios, the way younger photographers talk about wanting images that feel like “a scene from a film” rather than a lookbook.

Luchford once described the show as a way of pulling his whole world into one place so people could see the connections for themselves. Taken that way, Atlas was less a victory lap and more a map skate parks to Prada, punk gigs to Gucci, teenage film obsession to global campaigns. If you work in images, you have probably stolen from that map already. If you simply love fashion, chances are you have been moved by a Glen Luchford picture without even knowing it.

And that is the real measure of a legend. Not just that everyone knows his name, but that his way of seeing has quietly become part of how we all see.