Beyond Barbenheimer

In the world of Margot Robbie, a cup of tea is not just a beverage; it is a universal problem solver, a celebratory toast, and a grounding ritual all rolled into one. She has famously admitted to drinking at least ten cups of Dilmah a day, a Sri Lankan brand she carries with her to every film set and hotel room in the world. As she told Harper’s Bazaar, “In our family, a cup of tea is the answer to everything. When you walk in, you get offered a cup of tea. If something goes wrong, someone will be like, ‘I’ll make you a cup of tea.’ If something good happens, they will be like, ‘Great! We’ll make you a cup of tea.'”

This habit is rooted in a specific family tradition where tea is the standard response to any life event, whether it is good or bad. It is this specific, unpretentious Australian sensibility, the idea that you can be at the absolute centre of the cultural zeitgeist and still worry about whether the water is at the right temperature, that has made Robbie one of the most formidable and strangely relatable forces in modern cinema.

Robbie is a self-described tea fanatic with a very particular, almost industrial brewing process that she defends with the same intensity she once applied to sandwich condiments. She told British Vogue that while she loves America, it is hard to get a good cup of tea there sometimes. Her ritual is precise: the tea bag goes in first, followed by boiling water. She lets it steep until it is strong enough to handle the next steps, adds a spoonful of honey—never sugar—and stirs while the bag is still submerged. Only after the bag is removed does she add the milk. She has admitted that she and her husband, Tom Ackerley, have actual arguments over the proper way to make a brew, often instructing others to make hers “like they are making it for a small child,” meaning really milky and sweet. During the filming of Barbie, this obsession took a wellness turn; she and the cast drank milk thistle tea brewed for twenty minutes until bitter to achieve a “glow from within.”

This groundedness traces back to a childhood that sounds more like an adventure novel than a typical Hollywood origin story. Born in Dalby and raised primarily on her grandparents’ farm in the Currumbin Valley, Robbie spent her youth navigating the red dirt of the Gold Coast hinterland. She was not exactly a delicate child, spending weekends boar hunting and surfing with her three siblings. “I’m from a family where you’re a doctor or you’re in business,” she told CBS Sunday Morning. “I was just like, ‘I’m going to be an actor.’ And my mum’s jaw hit the floor.” Her mother, Sarie Kessler, a physiotherapist who raised four children largely on her own, was the backbone of the family. Robbie’s childhood was outdoor, practical, and slightly chaotic, an upbringing she once remarked was the last thing you would expect to lead someone into acting.

It was during these years that she earned the nickname Maggot, a name born from a teacher’s clumsy roll call mispronunciation that she, with typical lack of vanity, simply let stick. “I was about eight, and a teacher read my name out wrong,” she recalled. “I just didn’t correct her, and it stayed for years.” Even today, the name occasionally resurfaces among old friends, a reminder of the girl who was as comfortable on a trapeze, earning a certificate at age eight, as she was on a surfboard. After her parents divorced, she attended Somerset College, where she began to take drama more seriously, but the agricultural influence of the farm remained a constant. She has often noted that she was not a delicate child, but rather one who was obsessed with the mechanics of how things worked, whether that was the biology of farm animals or the structure of a good joke.

That early appetite for work translated into a three-job hustle by the time she was sixteen. She was cleaning houses, waitressing, and working as a “sandwich artist” at Subway. She talks about that Subway gig with a level of professional pride that most people reserve for their directorial debuts. “I watch them make it badly—and I’m upset,” she admitted on Hot Ones. For Robbie, it was about the edges. She has spoken at length about her frustration with people who do not spread the ingredients all the way to the crust, ensuring that every bite has the right ratio of everything. “It kills me. I don’t go that often anymore because I watch them make it badly—and I’m upset.” It is a funny anecdote, but it is the key to understanding how she runs a multi-million dollar production company today. She is a details person to her core.

When she finally decided to pursue acting, she did not wait for permission. She moved to Melbourne at seventeen and effectively cold-called the casting office of Neighbours until they gave her a shot. She landed the role of Donna Freedman and treated it like an insane machine, initially unaware that most people on the show did not have to clean houses on the side. “I’d been there for months before I realised that nobody else had other jobs,” she recalled, calling the realisation that acting could be a full-time career an “epiphany.”

However, even as she secured a role on an iconic Australian soap, she was met with a surprising hurdle: she was considered “too Australian” for Ramsay Street. During a 2026 appearance on The Graham Norton Show, Robbie joked about how she needed voice training because her natural Queensland accent was considered too strong. “When I started on TV I had to have a dialect coach because I come from Queensland and I was thought too Australian for Neighbours!” she laughed. “I couldn’t hear I had a bad accent, but they said, ‘You are just awful to listen to!'” She later elaborated in Vogue Australia that “they hired a dialect coach to make me sound less Australian, even though I was still playing an Australian character.” This early feedback didn’t discourage her; instead, she treated it with the same spreadsheet-level precision she used to track the money she owed her mother. She famously kept a written list of every dollar her mom had taken out of the mortgage to help her get started. “Everything I owed my mum, I had it written down,” she told CBS Sunday Morning. As soon as she hit it big, she wiped that debt clean and paid off the entire mortgage. “I just paid that whole mortgage off completely. I was like, ‘Mum, don’t even worry about that mortgage anymore. It doesn’t even exist anymore.'”

The transition to Hollywood was catalysed by a role in The Wolf of Wall Street, where she played Naomi Lapaglia. But Robbie secured the part by doing something that shocked the room: she slapped Leonardo DiCaprio. During her final audition, she realised she had about thirty seconds to make a mark. “In my head I was like, ‘You have literally 30 seconds left in this room and if you don’t do something impressive nothing will ever come of it,'” she told Harper’s Bazaar. Instead of following the script and kissing him, she whacked him in the face and screamed, “F—k you!” The room went silent. “I was like: ‘You’re going to get arrested. I’m pretty sure that is assault, battery. You will go to jail for this, you idiot.'” Instead, Scorsese and DiCaprio burst out laughing, and she got the job. Scorsese later remarked that she clinched the part by “hauling off and giving Leonardo DiCaprio a thunderclap of a slap on the face, an improvisation that stunned us all.”

Despite the immediate global fame that followed, Robbie refused to pivot into the glossy Hollywood lifestyle. She famously spent her early twenties living in a shambolic four-bedroom share house in Clapham, London, nicknamed “The Manor.” While she was filming blockbusters like Suicide Squad, she was coming home to six roommates and a frat-house energy. “I like living with lots of people. It reminds me of the house I grew up in,” she said. Her co-stars were often baffled; Alexander Skarsgard remembered being stunned that she was sleeping in bunk beds in youth hostels during her weekends off. She even bought a tattoo gun on eBay and began giving her friends matching “toe-toos,” a hobby she eventually retired after misspelling “skwad” on a crew member.

It was in this scruffy London kitchen that LuckyChap Entertainment was born in 2014. The group had moved in together to be affordable to the lowest-paid crew member in their circle. “The most frustrating thing is picking up a script and loving the roles in it except the female ones,” she once noted. “It’s really annoying and something I’ve striven to change.” Despite the masculine name, a drunken invention at the Wolf of Wall Street London premiere, the company’s ethos was firmly rooted in female agency. Robbie had grown tired of reading scripts where her character existed only to support a man’s journey. She once said she knows her look is more “toothpaste model as opposed to artsy,” which she felt was a shame because she wanted to play those messy, interesting roles.

They established a blunt rule for their projects: “If it is not a f—k yes, it is a no.” This filter ensured they only took big swings, like I, Tonya. Robbie did not even know Tonya Harding was a real person when she first read the script; she thought it was fiction. When she realised the reality, she trained on the ice for four hours a day, five days a week. “All the reading, all the acting coaching, and then someone reviews the movie… and all they do is focus on the aesthetics,” she lamented. “You think, ‘f—k you. You’ve totally discredited the work I did, and it’s not fair!'” The film earned an Academy Award for Allison Janney and proved Robbie was a formidable producer who could turn a messy story into a critical darling.

That success paved the way for the Lucky Exports Pitch Program in 2019, where Robbie helped six female writers sell action scripts to major studios. She has always framed this as good business, believing that if you give talented women the resources to write high-octane stories, the market will respond. Robbie’s reputation as a producer is not ceremonial; she is known to be cc’d on every single email, diving into schedules and budgets with the same intensity she once applied to sandwich condiments. This precision is visible in her physical preparation as well. For Suicide Squad, she learned to hold her breath underwater for five minutes for a single scene because she felt it would look more authentic.

This brings us to the Barbie era, which turned a toy adaptation into a shared cultural moment. Robbie was the architect who pitched the idea to Mattel and protected Greta Gerwig’s singular vision. “I kept saying to boards, ‘This is the most globally recognised word next to Coca-Cola. Everyone knows Barbie. This will hit!'” When the film was set to release on the same day as Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, she stood her ground. “I was like, ‘We’re not moving our date. If you’re scared to be up against us, then you move your date!’” She viewed the resulting “Barbenheimer” phenomenon as a gift from the public. “People kept asking me, ‘So is each marketing department talking to each other?’ And I was like, ‘No, this is the world doing this!'” She told Deadline that the timing was key because “the temperature in the world just really wanted the big injection of joy that the movie represents.”

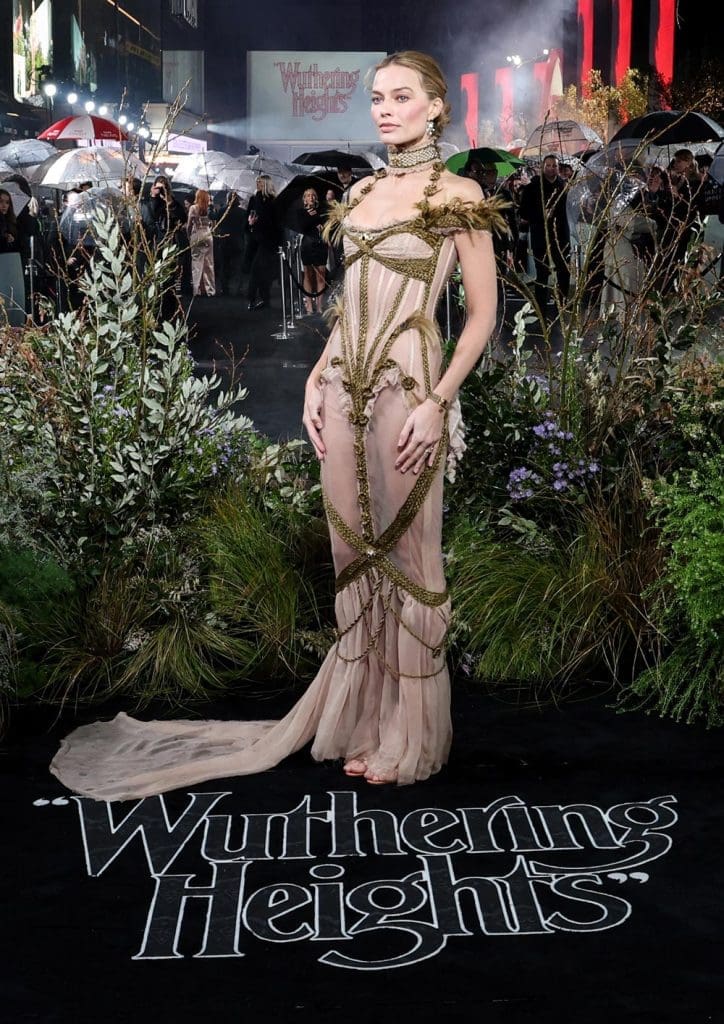

But true to form, as soon as she conquered the world of neon pink, she pivoted back to something darker and more abrasive. In early February, her and Emerald Fennell’s adaptation of Wuthering Heights arrived in cinemas. Predictably, it was loud and divisive. The film was described by Robbie as “sadomasochistic and desperately sweet.” She did not try to sand down the edges of the classic’s brutality. Starring alongside fellow Queenslander Jacob Elordi, Robbie leaned into the intensity of Cathy’s heart. Critics noted the film was dizzyingly stylised, finding eroticism in everything from grass to runny egg yolks. Speaking to Reuters, she noted the irony of two kids from the “Sunshine State playing the most iconic emotional disasters in English literature on the rainy moors of Yorkshire.”

The press tour for Wuthering Heights in 2026 was filled with unhinged stories. Robbie admitted to feeling “codependent” with Elordi on set, joke-calling him her “blanket” and saying she felt unmoored whenever he was not in the vicinity. Elordi, in turn, praised her professional calm, noting that he spent his time watching her drink tea and eat food, waiting for her to come undone, only to realise that she never does. Robbie defended the casting of Elordi, noting, “He’s the new Daniel Day-Lewis.” Of the film’s provocative nature, she told Vogue, “Everyone’s expecting this to be very raunchy. I think people will be surprised… it’s more romantic than provocative.”

This expansion of her influence took a major leap in January 2026 with the launch of LuckyChap International. Headquartered in London, this new division was established as a joint venture with the Mediawan Group. Robbie framed this as a pivotal step in LuckyChap’s development, bridging the creative industries of America and Europe to produce premium content that reflects their signature “mischievous DNA.” The upcoming slate is a testament to Robbie’s belief in big, risky ideas. High on the list is the film adaptation of The Sims, described as being somewhere between The Lego Movie and Barbie. Robbie is also shepherding a Monopoly movie with Hasbro, which she believes will be her next blockbuster. “Monopoly is a top property, pun fully intended,” LuckyChap stated, expressing excitement about bringing the game to life with a “clear point of view.”

Underneath the billion-dollar box offices is a serious work ethic, but also some work-life balance. She maintains a “three-week rule” for her marriage with Tom Ackerley, ensuring they never go longer than twenty-one days without seeing each other. She also makes time for her gin brand, Papa Salt, born from her share house days. “We weren’t drinking the nice stuff. And not always in the nicest bars,” she told Forbes Australia. She famously shared a trick from her backpacking days: “If you put a vanilla rooibos tea bag in your G&T, even the worst gin would taste fantastic.” It is a detail that fits perfectly with her image as someone who can find a clever, practical solution to any problem.

Looking at her trajectory from a Dalby farm to the big screen and the boardroom of LuckyChap International, it might just be the lack of a star ego that remains her most effective tool. She views fame as a currency to be spent on interesting art. She still talks about herself as being lucky to be in the room, but the reality is that Robbie made the room herself. As she moves deeper into 2026, navigating the fallout of her Wuthering Heights release and the expansion of her global empire, she continues to push boundaries. She never wants to get comfortable. She remains the person who shows up, spreads the condiments to the very edge of the sandwich, and stays grateful that “the whole ridiculous machine” keeps letting her in the door. Maybe the lesson is: do the work, stay grateful, and for God’s sake, make sure you put the kettle on.