10 Of Our Favourite Zaha Hadid Designs

It’s been 10 years since Zaha Hadid’s death, and it still feels strange to write about Zaha Hadid in the past tense. Not only because her designs seemed so futuristic but because her ideas are still happening. Walk through any major architecture school today, or any large practice with a computational design team, and you can see her fingerprints on every fluid form and convention-breaking thinking.

Hadid died suddenly in Miami in 2016 after contracting bronchitis and suffering a heart attack while being treated in hospital. Her sudden passing shocked the industry. Here was a designer who spent decades turning “impossible” into buildings and also in many ways fighting convention.

For a long time architecture spent a long time treating the right angle as a moral position. Hadid treated it as one option among hundreds. “There are 360 degrees, so why stick to one?” She also did it while carrying the extra weight that still sits on women in male-dominated fields: the constant scrutiny and the double standards: “If I was a guy, they would think I’m just opinionated. But as a woman, I’m ‘difficult.’” But Hadid refused to sand down her edges to make the room more comfortable. She had standards, she stated them, and she expected the world to meet them.

She was born in Baghdad in 1950, studied mathematics at the American University of Beirut, and then began her architectural education at the Architectural Association in London in 1972. The maths component became an important part of her work as an architect. She wasn’t frightened by complexity. She was fluent in it. By 1979, she had established her own practice in London, Zaha Hadid Architects, and for years, she built a reputation through competition-winning and theoretical work that became legendary even when it remained unbuilt.

Early in her career, she was treated as a “paper architect,” but in many ways, the tools, procurement systems, and construction confidence weren’t ready for what she was already producing. Then the world caught up. Modelling software, fabrication and structural engineering matured, and clients developed an appetite for cultural architecture that felt like the future rather than a replica of the past.

Working with office partner Patrik Schumacher, her focus was often described as the interface between architecture, landscape, and geology, integrating innovative technologies that resulted in unexpected, dynamic architectural forms. Her buildings often feel formed rather than assembled, as if shaped by forces, lift, flow, pressure, erosion, rather than stacked components. Growing computational capability also helped to translate complex spatial ideas into buildable systems.

Her first major built commission was the Vitra Fire Station in Weil am Rhein, Germany (1993). And it proved that a Hadid drawing could become a Hadid building, with all the tension and motion intact.

After that, the portfolio stacked quickly into a kind of study about complex, fluid space. The run that defines that pursuit includes MAXXI: Italian National Museum of 21st Century Arts in Rome (2009), the London Aquatics Centre for the 2012 Olympic Games (2011), and the Heydar Aliyev Centre in Baku (2013). Alongside them sit the works often hailed as future-shifting because of their visionary spatial concepts and the advanced design, material, and construction processes required to build them, including the Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati (2003) and the Guangzhou Opera House in China (2010).

The world also took notice. In 2004, she became the first woman to be awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize. She twice won the UK’s most prestigious architecture award, the RIBA Stirling Prize: in 2010 for MAXXI, described at the time as a mature work whose calmness belies the complexity of its form and organisation, and again for Evelyn Grace Academy, recognised for being expertly inserted into an extremely tight site and for what it signals to students, staff, and local residents, that they are valued, with student participation visible throughout the building. Her other honours included France’s Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, Japan’s Praemium Imperiale, and in 2012, she was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire. She was made an Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and a Fellow of the American Institute of Architecture.

She also carried a serious academic life alongside practice, holding roles including the Kenzo Tange Chair at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design and the Sullivan Chair at the University of Illinois School of Architecture, and teaching studios at Columbia University, Yale University, and the University of Applied Arts in Vienna.

In early 2016, she was awarded the RIBA Royal Gold Medal, the first woman to receive the honour in her own right. In the citation, architect Sir Peter Cook argued that her work wasn’t a trend but “a substantial body of work rather than… work which is currently fashionable.” He described her as someone who “ventured where few would dare,” he then seemed to sum up her journey: “Zaha took the surfaces… out for a virtual dance… then took them out for a journey into space.” She had the imagination to invent new spatial languages, and the discipline to see them built.

Messner Mountain Museum Corones, Kronplatz (Plan de Corones), South Tyrol, Italy (2015)

Messner Mountain Museum Corones is one of Hadid’s more restrained designs but for very good reason. The museum is embedded in the summit at 2,275 metres, with only a few sculpted “openings” pushing out toward the views, as if the building is using the mountain as its structure and its drama. The design philosophy centres on “submerged architecture,” where the building uses the mountain as its primary structure. Hadid noted that “the idea is that visitors can descend within the mountain to explore its caverns and grottos,” before emerging onto a cantilevered terrace. Only the reinforced concrete canopies are visible from the exterior, oriented specifically toward the peaks that defined Reinhold Messner’s famous climbing career.

Dongdaemun Design Plaza (DDP), South Korea (2014)

This project functions as a “metonymic landscape” that replaces traditional city blocks with a continuous, walkable surface. The exterior skin consists of 45,000 unique aluminium panels, managed through Building Information Modelling (BIM). Hadid designed it as a 24/7 urban infrastructure, stating, “I don’t think that architecture is only about shelter… it should be able to excite you, to calm you, to make you think.” The site incorporates the ancient Seoul fortress walls into a fluid, neofuturistic layout that erases the boundaries between building and park. It is famous for proving that complex geometry doesn’t have to be private “icon” architecture, it can be everyday usable urban infrastructure.

Guangzhou Opera House, China (2010)

Known as the “twin boulders,” this project features two volumes clad in triangular granite and glass panels. The design was shaped by the erosive forces of the Pearl River, echoing Hadid’s view that “architecture is really about well-being.” The main 1,800-seat auditorium is housed within a complex steel space frame and features a “thousand-star” LED ceiling. The project focuses on “porosity,” using ramps and folds to link the performance spaces directly to the riverside park.

Photo credit: Virgile Simon Bertrand.

Nordpark Railway Stations, Austria (2007)

These four stations use a “shell and shadow” logic, where lightweight glass canopies sit atop heavy concrete plinths. The forms were inspired by glacial ice formations and manufactured using CNC milling techniques from the automotive industry. Hadid explained that “each station has its own character, yet they all belong to the same formal family.” This project demonstrated that industrial infrastructure could be highly expressive, proving her point that “architecture is how the person places herself in the space.” It’s also proof that “infrastructure” doesn’t have to look like a cheap design-by-committee affair.

Photo credit: Werner Huthmacher.

BMW Central Building, Germany (2005)

Designed as the “nerve centre” of a manufacturing plant, this building integrates production with administration. Car bodies move along 600 metres of open conveyor belts directly above office spaces, making the industrial process visible to all staff. Hadid sought to dissolve traditional corporate hierarchies, stating that “the offices and the factory are no longer separate entities.” By treating circulation as the primary driver, she turned the logic of an assembly line into a dynamic spatial experience.

Photo credit: Helene Binet.

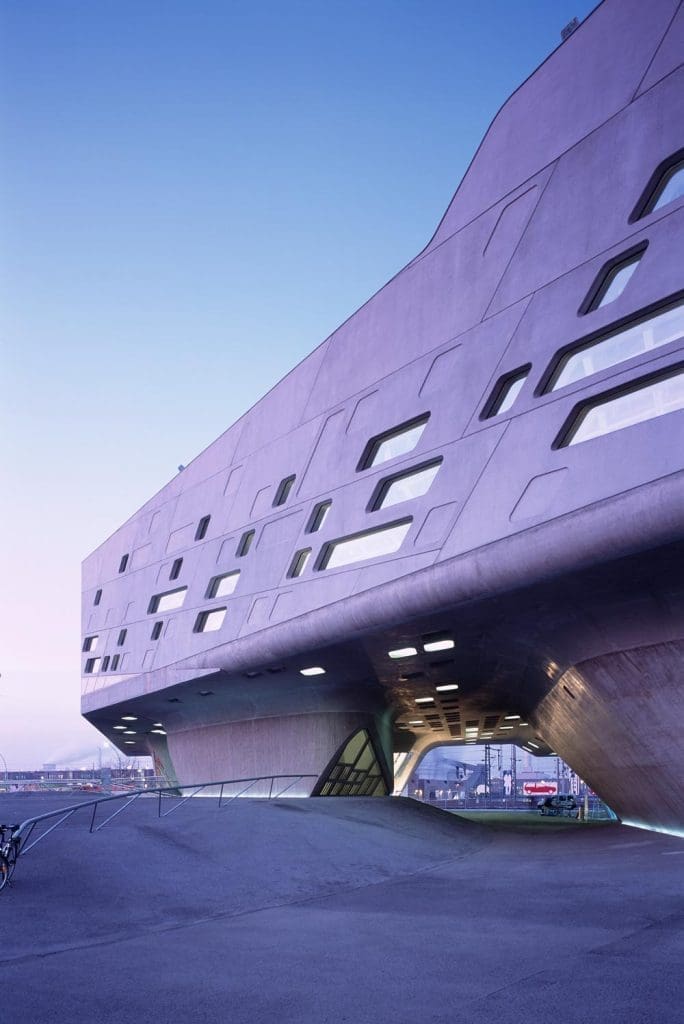

Phaeno Science Centre, Germany (2005)

looks like a building being lifted by forces you’re meant to learn about inside. It’s an interactive science museum where the structure does some of the teaching. The Phaeno is raised on ten massive conical concrete structures, creating a covered public plaza underneath. These cones house internal functions like a bookstore and theatre. Hadid described the project as “the most complete statement of our quest for complex, dynamic and fluid spaces,” where the floors shift and warp to create varied viewpoints. It remains one of the most complex cast-in-place concrete buildings in Europe, utilising the material to create sharp angles and long spans that seem to defy standard physics.

Photo credit: Werner Huthmacher.

Pierres vives, France (2012)

This “City of Knowledge” combines a library, archives, and sports administration into one 200-metre-long structure. The design uses the metaphor of a tree: the archive is the trunk, the library is the branches, and the administration is the foliage. Hadid applied her “parametric” logic to this civic programme, asserting that “you have to really believe not only in yourself; you have to believe that the world is actually much better than you think it is.” The facade uses glass and pre-cast concrete to signal the varying levels of privacy within.

Photo credit: ZHA.

Vitra Fire Station, Germany (1993)

This was the project that proved Hadid’s radical drawings were structurally viable. The design consists of sharp, intersecting planes of exposed concrete with no right angles, intended to keep firefighters in a state of “alertness.” Hadid reflected on this period saying, “I used to try to curate a building, but now I let the building curate the landscape.” While it is now a museum, it remains a landmark for using “linear” geometry to define a small-scale, highly functional space.

Photo credit: Christian Richters.

MAXXI Museum, Italy (2010)

Moving away from the “museum as a box,” Hadid designed MAXXI as a series of intersecting “galleries-as-streets.” The building functions as a delta of curved concrete tracks that overlap, mirroring her philosophy: “I don’t think you can teach architecture. You can only inspire people.” The interior features black steel stairs and neutral concrete walls, allowing the architecture to serve as a high-contrast backdrop for contemporary art while integrating into Rome’s urban fabric.

Photo credit: Iwan Baan.

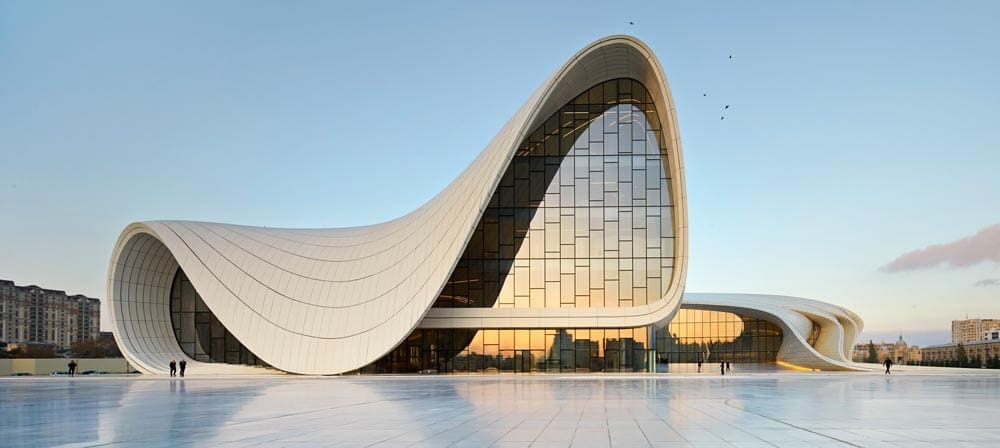

Heydar Aliyev Center, Azerbaijan (2012)

This building is a study in architectural continuity, where the ground, wall, and roof are treated as a single surface. It was designed to contrast with the rigid Soviet modernism of Baku, reflecting Hadid’s belief that “the world is not a rectangle.” The structure utilises a space frame system to create massive column-free interiors, including a 1,000-seat auditorium. The white, undulating shell is made of glass-fibre-reinforced concrete (GRC) panels, allowing the building to appear as if it is “unfolding” from the landscape.

Photo credit: (Exterior) Hufton+Crow, (Interior) Iwan Baan, (Auditorium) Helene Binet.